Kids, household tasks and that feeling that the sun is inside you

/About childhood chores, I remember mostly boredom--a million cherries pitted, a thousand apples picked, countless weeds pulled, endless Saturdays spent scrubbing the bathroom, vacuuming and--longest of all somehow--cleaning my own room.

But then there was apple juice spilling from the spout of the press. The first drink--so rich it makes your teeth ache, yet it slides down your throat like perfect music.

There was the realization that my classmates in college didn't know what to do in a kitchen, being known as "the techie one" because I knew how to turn on a vacuum or unplug a drain--even though in reality I'm rather technically challenged. Today there is that sense of wonder at a basket of food grown with my own hands, food that was just seeds a few months ago and the realizations that I had learned this as a toddler.

Creative Commons image courtessy of Georgios Liakopoulos

Viral internet videos have made famous the 2014 Braun Research study which reports that only 28 percent of kids today do chores. People watch the cute pictures of three- and four-year-olds doing chores and cooking, and they gush about how important the skills and the theoretical sense of responsibility they gain is to those kids and to the world.

In my generation, just a few decades ago, the digits were reversed. 82 percent of the parents of today did chores as children. We have those memories of aching boredom, frustration and watching the sun slowly march across the sky, stealing our play time on a glorious, sunny Saturday. My husband recalls his own childhood on a South Bohemian farm as one endless era of forced labor in the garden beds, weeding and picking.

Sure, there are people out there who think parents who give kids chores are looking for cheap labor and they put negative comments on those chore videos. But I can pretty much guarantee that those people either aren't parents or they have never asked a kid to do a chore, because any parent who has knows the exponential amount of effort and work it takes to teach and persuade kids to do chores than it is to do it one's self. Even if the task is something kids want to do, like cooking a special treat, the amount of work parents do to "help" kids learn, do and clean up from the task is massive.

But the Braun study found something else interesting. Even though only 28 percent of kids today do chores, 75 percent of parents believe chores would help their children learn skills and gain responsibility.

So what is the problem in this generation? Parents believe it's good for kids to do chores but very few actually follow through. Why?

Creative Commons image courtesy of Darien Library

I can think of several reasons right off the top of my head:

- Parents are busy and over-stressed. It really does take several times the time and effort to teach or even persuade a child to do a task than to do it one's self. We don't have kids do chores in order to get things done faster, at least not for several years and even with older kids the stress involved can outweigh any minor time savings.

- Kids are busy. There is a social expectation that good, responsible parents will provide their kids with at the very least a sport, a foreign language and a creative experience. That means that on top of school and homework, kids are racing between soccer, Spanish and ceramics classes. Some say parents then feel guilty about giving kids chores on top of all this. I contend that the 15-hour, kids-awake-time day is simply over. Guilt of no guilt.

- Attachment parenting is all the rage and forcing is unfashionable. Last but definitely not least. a myriad of books and media today tell us that it is the emotional development of children that is most important to their future success and survival and that the only way to ensure their emotional health is to defer to their pure and natural desires and ensure that harsh words never pass our lips. Discipline is supposed to be all about "natural consequences," even thought they don't tend to materialize in the insulated, safe worlds of our homes. That doesn't leave much room for persuading kids do do boring tasks that no one without a couple of decades of experience can see the value in.

I am far from a perfect housekeeper, cook or gardener and not a day goes by when I find that I lack a skill that my mother tried to teach me. How do I make sure the meat is cooked all the way through? What cleaning tools or supplies might help in scraping and scrubbing some of those deep, dank corners? Why aren't my pumpkin plants sprouting this year?

I do know the basics of gardening--soil, compost, seeds, water. It's simple right?

Well, actually it isn't. After ten years of trying, I'm now just barely a decent gardener. And when I remember my initial attempts to cook in college, having come from a mother who was famous for delicious and seemingly instantaneous meals, I laugh. I did know how to boil rice and fry eggs though, and watching young adults who don't have the slightest idea where to start with either task today is disturbing.

More disturbing is looking at more studies on human behavior. One of the longest longitudinal studies ever conducted on humans, the Harvard Grant Study, found that the factor most closely linked to professional success was the length and early on-set of childhood chores, i.e. the more chores kids did and the younger they started, the more successful they are as adults today.

It's an average, of course. There are a few kids who had it easy with no chores and were handed a high-paying job by their families and continue to manage not to screw it up. But most who didn't do chores, either don't make it to success or crash and burn if success is handed to them.

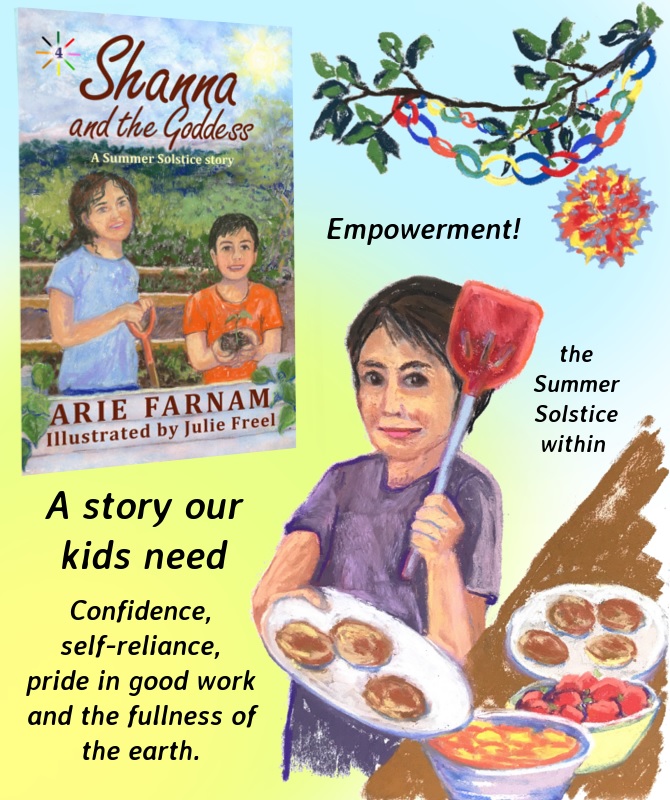

Illustration by Julie Freel from the book Shanna and the Goddess--a story about growing maturity and empowerment

And that study was done on the 82-percent-doing-chores generation, in which many of the 18 percent who didn't do any chores "failed to launch" and became the modern joke of "kids" over thirty who still live with their parents and can't seem to find their way. I'm not going to speculate about the generation with only 28 percent doing chores, because most disaster predictions turn out to be wrong. But yeah, it's disturbing.

One of my kids has special needs that make dealing with chores much more difficult than it would be with the average kid. The younger sibling is seven and still needs a lot of help doing household tasks. I know the stresses and strains and doubt I'll live up to a perfect standard or teach my kids even as much as my mother taught me.

But I'll try. Not just because I want my kids to be successful (or at least move out by the age of thirty). More important than that to me is the feeling I get from knowing how to do things that take care of my home and food.

It's primal, I think. It is one of the most intoxicatingly empowering feelings, the sense of competence. The sun is inside me when I cook a great meal in record time or pull in the first garden harvest of the year or take a deep breath and look around at that brief moment when my house is clean before the kids demolish it again.

It is very good to be self-reliant and competent. And kids get the same sense of that, even with smaller tasks. Of course, I didn't love chores as a kid, but I did love the feeling of the sun shining inside that came at the end. Just like he endorphins after exercise, it is a reward you don't know will come until you've done it often enough.

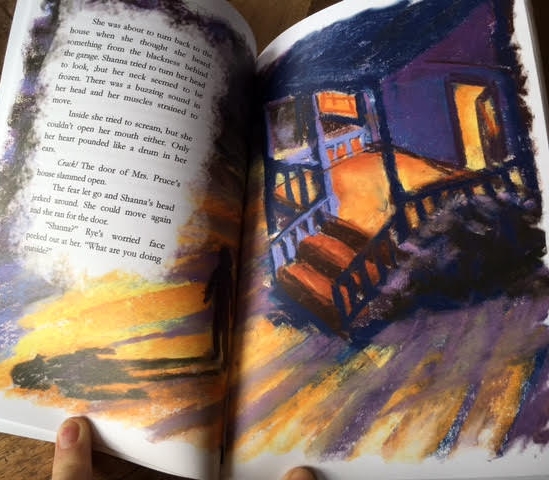

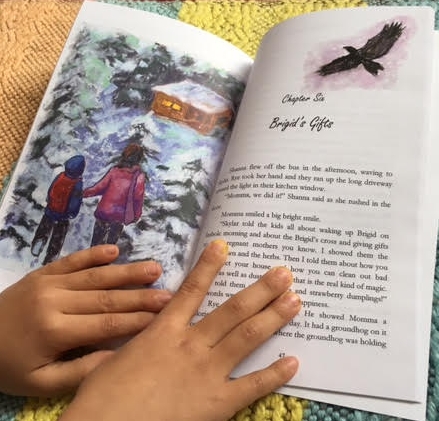

When I write children's stories, my goals are to connect with kids through fun, suspense and things that make them feel good about themselves and their values. Our latest children's story, Shanna and the Goddess, goes right too that feeling of confidence and empowerment. In this illustrated, chapter book, a brother and sister named Shanna and Rye must take on significant. grown-up responsibilities when their single mother breaks her ankle. These modern-day kids start out eager to help, but soon they face hard work, callouses, conflicts and a destructive hail storm. They weather these troubles and receive much deserved rewards.

Shanna and the Goddess is also a story of the modern-day celebration of the Summer Solstice, the day of the longest and most intense sun. The story reflects the natural power and expression of the height of summer through the story of growing maturity and the children discover the sun within as a personal source of empowerment.