Reclaiming Pagan identity

/"I'm not a Gypsy!" a thirteen-year-old boy in a Romani (otherwise known as Gypsy) settlement in Eastern Europe once told me. "Do I look like I have some kind of free and easy life? I don't have a wagon or one of those funny round guitars."

I was a journalist at the time--supposed to be impartial and not interfere with the natural course of events--so I didn't do what I wanted to do. I have since regretted that I didn't put an arm around the kid's shoulders and say, "I hear ya, brother. I know what it's like to have your identity usurped and dragged around to serve various fashion trends and self-indulgent subcultures. Don't let that stop you from knowing who you are."

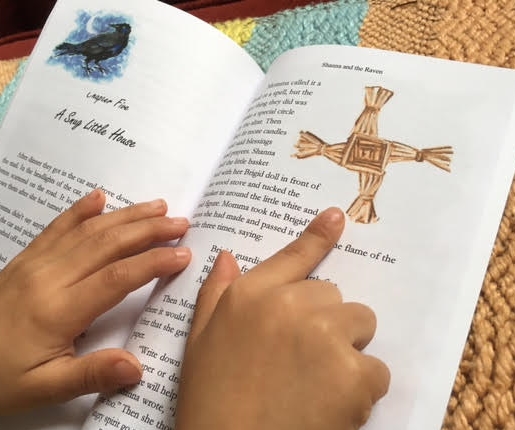

I do know because my identity is bound up with similarly loaded words. And when I first started writing Pagan children's books that was the greatest obstacle I faced. Many people who I expected to be supportive (because I grew up with their earth-centered spirituality) were skeptical and even resistant to the idea.

A Pagan symbol from Latvian mythology of the Sun Tree -- Creative Commons image by Inga Vitola

"If you use words like 'Pagan' or 'magic' or 'witch,' you're going to limit the types of people who will read the book," one critic told me in no uncertain terms. "And a cauldron? I mean seriously! I can't believe you called it a 'cauldron.'"

Other times I've heard people who clearly practice earth-centered spirituality say essentially the same thing that the Romani boy told me. "I'm not Pagan," one said. "When people hear 'Pagan' they think about immature mind games, hedonism and irresponsibility. It's the sort of thing that teenagers play around with just to annoy their parents. It's not a serious earth-centered spirituality."

There are always tough decisions to make when presenting a book to the world and foremost among them is "Who am I writing this for?" I had to keep that question firmly in mind as I navigated the publishing process for Shanna and the Raven.

The answer is that I wrote it for Pagan and earth-centered families. I want people who share these beliefs to be able to find the book using those search terms. And I'm not as interested in what everyone else in society thinks those terms mean.

And moreover, I have two children myself and I think about what it meant to me to grow up with an identity that had no socially acceptable name.

Why "Pagan?"

I know there are a good number of people in the United States, Europe and Australia who accept the term "Pagan" readily. However, the fact is that there are many more people (possibly several times our number) who share our essential beliefs yet don't accept that term. That's why it's worth addressing the issue of why I use the specific term "Pagan."

I grew up with earth-centered spirituality but I didn't adopt the term "Pagan" until I was about thirty. That was mostly because I spent many years looking for a word that could accurately convey my meaning. Over the past twenty years many terms have become well-known--some ultra specific like "Wiccan," "Druid," "Asatru" or "Reconstructionalist." Some vague or only used by some, such as "New Age" or "goddess culture."

I chose the term "Pagan" for one simple reason. It is broad enough, yet to those who accept it, it means what I am trying to express. Thus if I find someone who identifies as Pagan and I say that I am Pagan, we both have a rough idea of what that means. Not perfect, no. But look at the wild diversity of Christianity or Islam. We're hardly alone in not being uniform.

The term "Pagan" is also used in a specific way by serious news media. In the code of newspaper journalism, one should call a group "Pagan," if it represents an indigenous belief system with strong ties to nature and probably several gods or goddesses. Recently I have seen newspapers refer to tribes enslaved by ISIS as "Pagan" because they fit those criteria. Thus the term "Pagan" Is not exclusive to indigenous European religions, although it is most often used that way.

I know I'm treading on dangerous ground among fellow Pagans, asserting that I have a firm definition for the term "Pagan." But it isn't so much that I have that definition myself. It is that I accept and identify with the standard definition of the term. I don't fight the meanings of words because the most popular definitions of words will prevail in over time and resistance in this case really is futile. If I had come of age and discovered that most people called the beliefs I hold "gobbledygook" I would have identified with that term and fought for its correct interpretation and positive identity. Thus I don't fight against the term but rather for its clearer understanding.

Get the Pagan children's book Shanna and the Raven here.

That is why I use the term "Pagan" both for myself and to my children and in my children's books. Yes, "Pagan" originally meant something like country bumpkin and it wasn't specific to a religious path. But it is now. It has a commonly accepted definition, whether we like it or not.

Gay used to mean happy. American Indian and Gypsy were both terms assigned to (and largely accepted by) whole nations of people based on someone else's poor grasp of geography. (Gypsy comes from the incorrect belief that the Roma came from Egypt.)

Seriously, we need to stop whining and be glad for the identity we have. Show me a better or more understood term, and I'll seriously consider it. But for now "Pagan" is the term we have. The term "Witch" is in a similar category, though the road to the broader understanding of that term will be even more rocky.

Why do we need an identity term?

There is another argument I encounter in the community discussion on this issue and that is that some people strongly believe that we don't need terms of identity at all, that these are just "labels" and actually potentially damaging. I do understand the idealistic and positive intention behind these concerns. We should all be human beings first--dwellers of this earth and universe, in kinship with every being.

But... you knew that was coming, didn't you? But we don't live in an ideal universe and neither do our children. The concept of rejecting all labels and merging into one big happy identity is akin to the argument for "colorblindness" among many white people in the United States or Western Europe. The lack of identity works just fine if there are truly no distinctions or problems between people in society. However, if there is any measure of tension, lack of identity works in favor of those associated with the largest and most privileged group and to the detriment of minority groups.

Get the Pagan children's book Shanna and the Raven here.

Many of those who embrace earth-based spirituality today grew up in another religion with a very distinct name, and part of their change is to release themselves from names and labels, so our community members often balk at terms such as "Pagan" or even "earth-centered."

It's understandable. However, there is an issue here that goes beyond the desires of individual spiritual development. These first-generation Pagans did grow up with an identity, one they could understand, make decisions about and even reject because it had a name. And they also grew up in the majority culture.

Children raised in earth-centered families are not fully in the majority culture and they often lack the words needed to make their own decisions about their beliefs. That was why out of all the worthy topics for children's books, I chose to devote my first books to stories of contemporary Pagan children.

As I write the second book in the Children's Wheel of the Year series I note that the only times identity labels are needed or even arise in these stories are when the characters encounter hostility from the majority culture. We could live happily without labels, if we lived in isolation. But we don't and our children don't. If you send a child out into the world after teaching them values and stories that are very different from those of the majority but give that child no words with which to think consciously about such things, you send the child into inevitable confusion and pain and cut the child off from a sense of belonging.

Psychologist Abraham Maslow defined a hierarchy of needs, beginning with physical needs for food, shelter and safety and culminating in self-actualization. The theory, which is used widely by psychologists, is that one cannot progress to higher levels without fulfilling the lower needs on the hierarchy. Thus to reach self-actualization an individual must have basic physical needs met. And directly above the basic needs of the body and safety is the need for belonging.

For children to fulfill the need for belonging in the majority culture, they must feel that their ideas, values and beliefs are supported and shared by others at least to some degree. The facts of today's world are that many Pagan children encounter not a world where labels don't matter but a world where their beliefs are disregarded or rejected and their celebrations are unknown or mocked. In such a world, children must still have belonging in order to reach self-actualization and that belonging comes from the understanding is that there is a community out there--though scattered--that shares and honors their values and stories.

That is why we need a Pagan identity.