Why do daily spiritual practice?

/It has been some time since I wrote about my daily spiritual practice. And I think it’s time I fully admitted that I have become a solitary Pagan, though I didn’t set out with this end in mind.

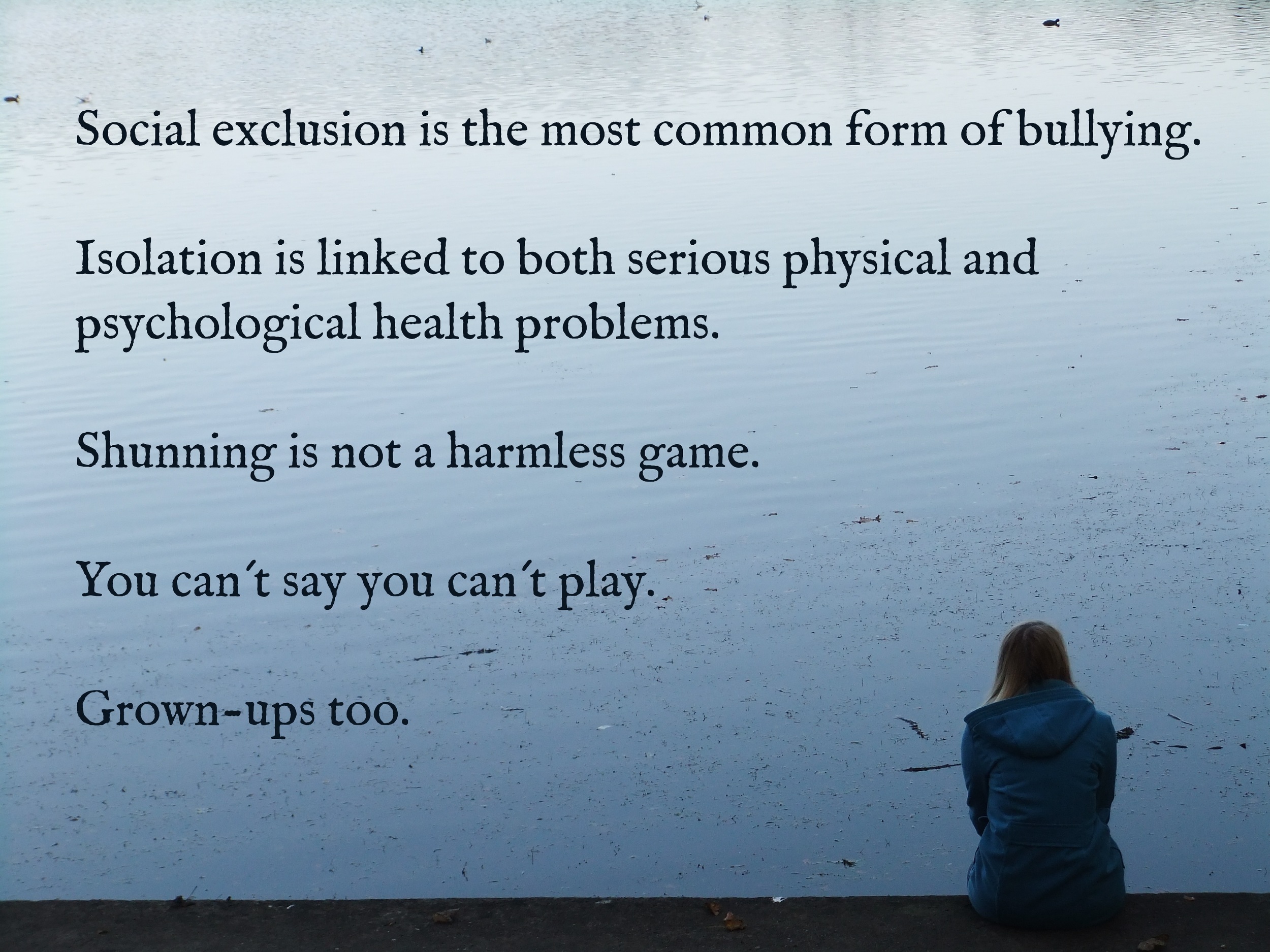

Those of my family and kin who practice a similar path are five thousand miles away. I was rejected by the only coven I ever actually managed to meet in person (supposedly because I wasn’t interested in angels). I tried to join several local Pagan groups and had to opt out of all of them because of either latent white supremacy or heavy-handed ego trips within the leadership.

There are no more publicly contactable groups to try within reasonable transportation distance. I tried to start a local group three times and was laughed off of forums and left alone with my circle of boulders that I had moved to my yard for this purpose.

And so here I am. Just me, my garden, my chickens, my big rocks and my emphatically disinterested husband and children.

I once hoped that my spirituality might bring me community, mutual support, friendship, family unity and even possibly a livelihood. Spiritual traditions and communities sometimes do bring these things and many of us want them. Some go into a religion or tradition specifically for the social standing, the image or a career.

I didn’t go in with a conscious agenda, but subconsciously I now think I did hope for at least the community part when I took up serious spiritual practice.

In a way, it might be a good thing in the end that my subconscious desires didn’t pan out. My spirituality has been stripped of all accouterments and fringe benefits.

It is what it is and what I get out of it will be only that which comes directly from the spirituality itself.

Do I really believe there are gods? Does my matron goddess really watch over me? Are the spirits of the land there and if so do they give a flying crap about my offerings? Does magic work in any shape or form? Does my spirituality matter at all? Does my life matter?

A solitary Pagan has to face the questions of the soul full on.

There are no pep talks and theory doesn’t matter much. From where I stand, what matters most is practice. And for me that means daily practice.

I have technically been a practicing Pagan since I was a kid, but for much of my life it was pretty sporadic. As a young adult, I was focused on my journalism career and traveling adventures. I had a tiny kit with a few stones and a traveling-spirit doll that I carried everywhere with me and propped up on window sills and against tree trunks from Ecuador to Nepal.

But in those years I didn’t ask the tough questions. Life was chaotic. But in one important way, it was easier. I had only myself to look out for.

Now times are harder in general and I have kids, a husband, students, animals, a garden and a house to look out for. I can’t avoid the tough questions any longer.

I’m in my third year of intensive daily practice. It has changed a little since I started but only in the details. And as a solitary Pagan it is the real heart of my practice, even if I occasionally do rituals with family members or friends as well as specific spiritual work elsewhere.

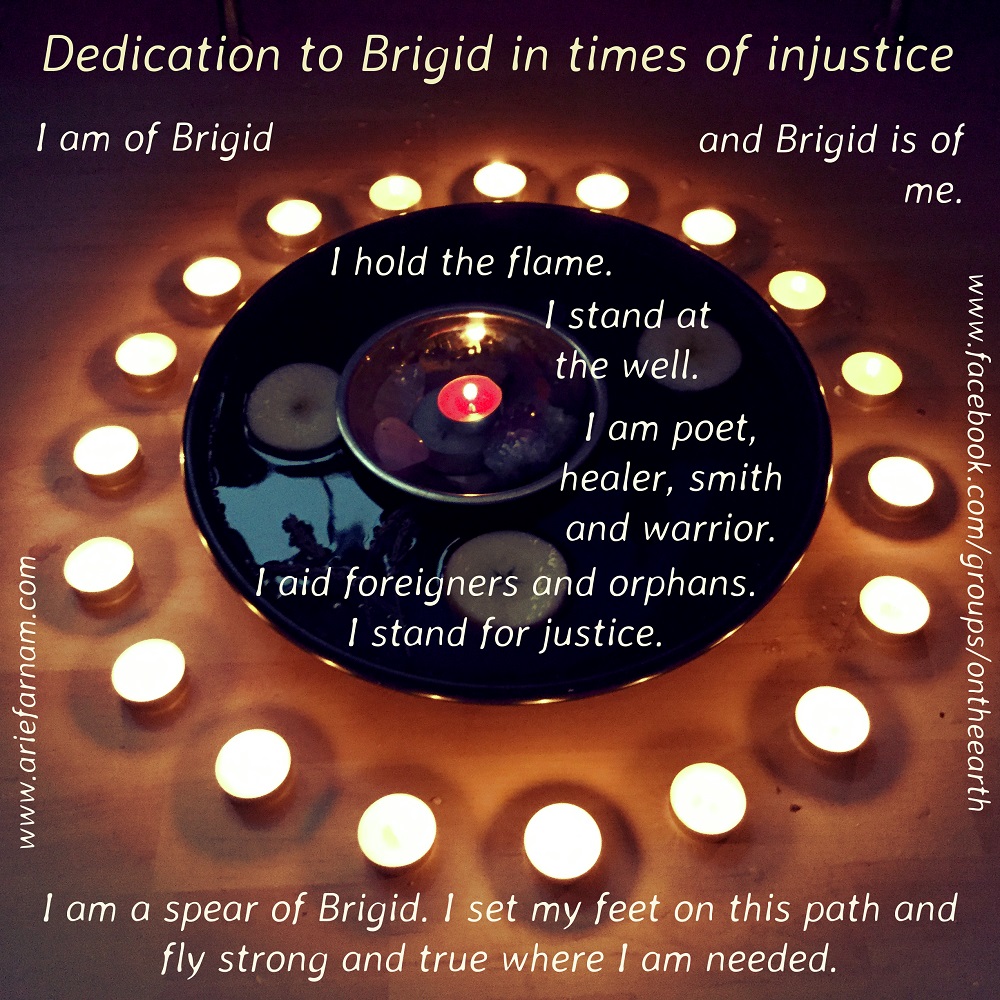

I do my main spiritual work in the morning, if possible before the rest of the family is awake. I light a candle on the altar by the hearth, say a quick greeting to the light of the new day and to the goddesses of light, burn a bit of a cleansing herb bundle and do a brief visualization for grounding, protection and blessings for ancestors and home guardians.

Then I get down the daily cards from the kitchen altar (a Tarot card drawn the day before and a card showing the exact moon phase) and take them (and a cup of green tea) to the main altar in my office. There I do a longer meditation focused on connection with my matron goddess. I make offerings, light candles and sip tea while reciting a chant.

I have been studying the goddesses of many cultures over the past two years. I study and make offerings to a different goddess each week. Then I renew the moon card and draw a new Tarot card for the day, which depending on how positive or negative it is I take as either a blessing or as guidance about potential pitfalls to be aware of during the day ahead. Then I write notes, noting down any divination or working I have done, making note of my daily Tarot card and physical and emotional state of being. I also write down the weather and outside temperature as well as whatever work I have done in the garden in my almanac and moon calendar.

These studies and notes keep me consciously aware of natural cycles and help to slowly improve my abilities in herbalism, gardening and divination.

When there is time I may follow up with a working for prosperity, artistic inspiration, healing, binding of threats or protection of my family, animals or garden or to celebrate the turn of the seasons. Occasionally I’ll do divination on a pressing question through Tarot, i-Ching, Runes or Ogham.

On good days, this practice leaves me feeling cleansed and invigorated, ready to take on anything. Not every day is a good day though. There are plenty of days when I have to hurry through my practice with little time for anything but jotted notes and rote recitation. On other days I’m slow to wake up, sick or nursing psychic wounds from the harsh social environment I live in.

On the hurried days, I go through the motions easily enough, now after so much recitation. Very rarely I devote just a few seconds and cut back most of my practice if I have to leave the house before six in the morning.

On the emotionally hard days, I muddle through, stopping and starting, spending overly long periods staring blankly at the wall or into a candle flame. Sometimes I cry or argue with my gods or question or rage in anger.

Not every day is good. In fact, the hard days seem to come ever more often. But I am rarely tempted to shirk my daily practice. The calming effect is clear, and beyond that, I like the warm glow of candles and the smell of herbs and incense. For those few moments, I feel that all is right in my world and that I can be who and what I have always wanted to be. The failures and disappointments of life fall away. The chaos is temporarily quiet.

Is that enough? Is that a good reason to spend 15 to 30 minutes in front of an altar every morning? My atheist husband sounds irritated and dismissive when he does mention my practice, which only happens in the context of arguments over who is more stressed and who should take on some new household task or problem.

If one truly believes there is nothing beyond the physical world and the zapping neurons in our brains, then we must rely only on the calming effects of this meditative practice to give it purpose. Supposedly it has health benefits, but it’s unlikely that I’m doing it to the specifications of whoever studies such things.

My thealogy is pretty shaky. I do believe there is more to the world than the physical realm. I have had bits and pieces of evidence of something beyond. But while I love and revere my goddess and enjoy studying goddesses of the world, I’m not exactly sure what I think a god or goddess is. I have theories—mostly pretty unorthodox theories. I want to believe in the Otherworld and the Good Neighbors or spirits of the land or both. I study on them but there are so many different perspectives and without a group to hold me to one line, it is easy to get lost.

I want to care for my ancestors, even though my personal ancestry is uninspiring. I still stand on their shoulders, whatever the price. And there are ancestors of my craft and of social justice movements that I honor.

Beyond all that, I have never managed to believe in a purely materialist reality. I don’t know for sure if my spiritual practice really brings me much more than some added calming, grounding and centering. I just know that when most of my life feels like I am carrying a backpack loaded with rocks, my spiritual practice lets me set it down briefly and it sometimes feels lighter when I pick it up again to go on with the day.

Before I committed to doing spiritual practice every day, the practice I did often felt like part of the load of rocks. It was hard to get to. It was one more task that I felt like I should do but often put off behind other more urgent practical tasks because it could technically wait. I’d go far too long without visiting my altar at all. My tools and books would get misplaced and it would then be much harder to return to it.

I made a commitment to do daily practice partly because the signals were that it was asked of me by my matron goddess and partly as an experiment. I am not certain how much it is a requirement from a goddess. I have missed a rare day or two in the past two years. Once I was truly too sick with an extreme flu that killed my mother-in-law and left my children severely dehydrated. And I didn’t get any irritation from my goddess.

It’s more the experiment part of the commitment that turned out to be important. Sure, it was hard at first. There were days I didn’t want to. I was tired and too busy. But I did it and after a while the struggle eased. Now this is one thing I don’t have to struggle over.

I feel incomplete without my spiritual practice and I enjoy it. In the end, that’s the bottom line. Why do daily spiritual practice? What is the purpose of spirituality?

It is good. It fills a need. It helps when things are hard and uplifts when things are good.