The Ostara story of the Children's Wheel of the Year is finally here!

/With no time to spare... but we made it. The Ostara story of the Children's Wheel of the Year series is out.

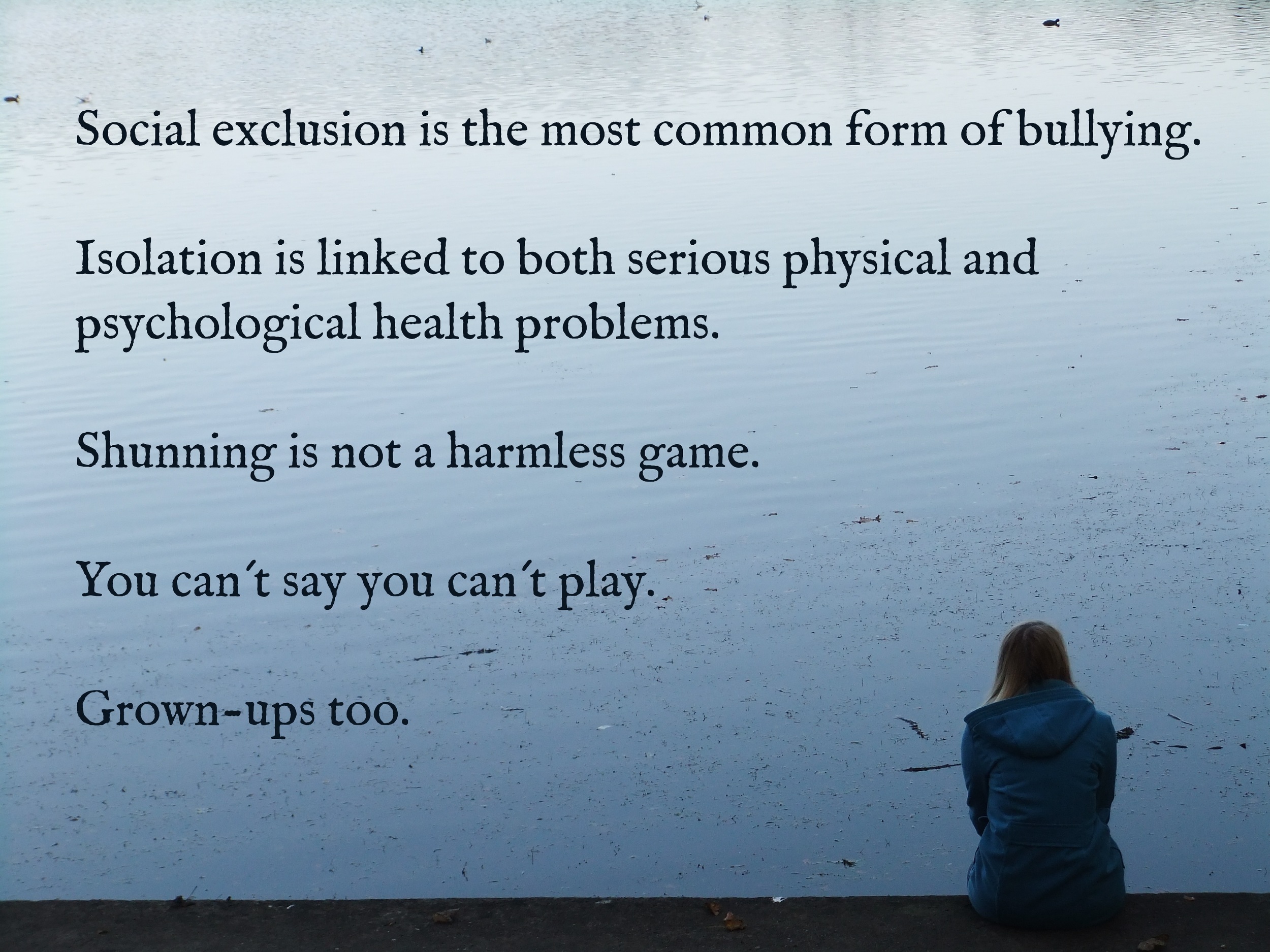

Shanna and the Pentacle is everything I hoped--an adventure story that will have kids rooting for the characters. It's also an example of how to deal with bullying problems and the often difficult new beginnings in life. There are more wonderful and evocative images by Julie Freel.

Here's the story:

The gift of a friend,

The promise of the pentacle,

A new beginning…

And the courage to stand your ground.

Ostara is a time for buds and shoots, for the smell of wet earth and for asserting your true self. A new beginning can be hard but it’s worth it after all.

Ten-year-old Shanna and eight-year-old Rye are starting out at a new school just before Ostara. A teacher notices Shanna’s pentacle necklace and asks her to take it off. Brandy, the popular girl, says Shanna is going to “hell” and Rye has his own trouble with kids who say boys don’t draw or sing. Still the magic of Ostara is at work. Shanna and Rye can meet new challenges and find new friends.

Like Shanna and Rye, children from earth-centered families often stand out in mainstream society. Without strong identity and confidence, they struggle to choose their own path. The Children’s Wheel of the Year books provide concepts our kids need to face these challenges.

The book is currently available in Kindle format and will be out in paperback and other digital formats next week. Look on the Children's Wheel of the Year site for minute-by-minute news about new formats.