When you were refugees

/Where I grew up in northeastern Oregon, you sometimes hear a lonely soul remember that our families were once refugees--long ago. There's a fugitive whisper of remembrance when the topic of conversation turns to immigration.

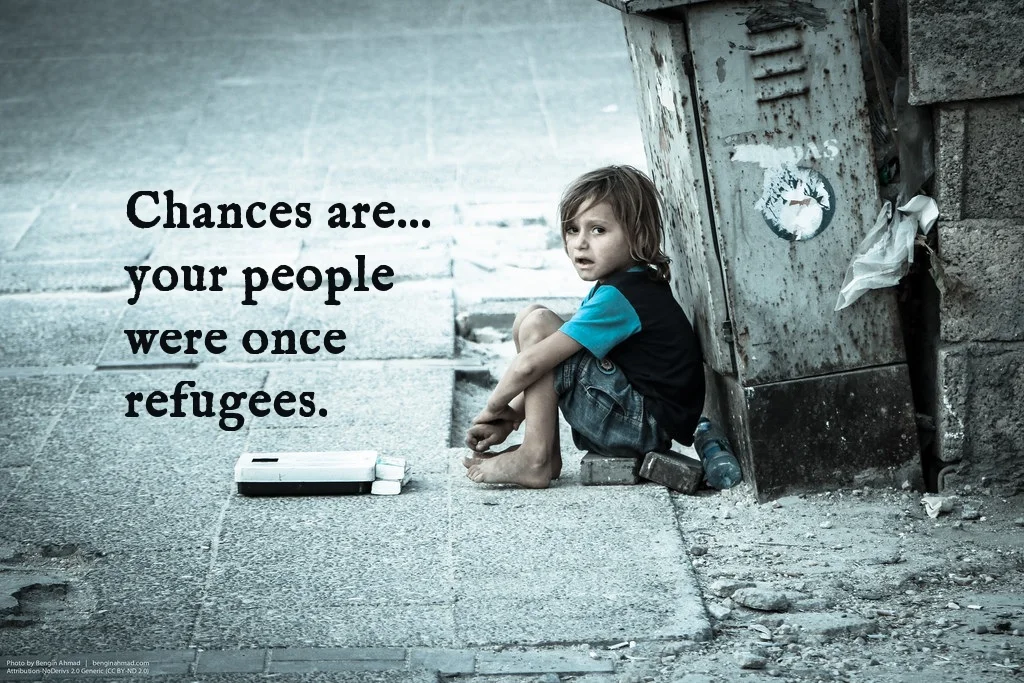

Creative Commons image by Bengin Ahmad

The images and stories of early American immigration are usually fairly heroic. There are the Pilgrims and then the Pioneers. They are portrayed as intrepid explorers facing terrible danger in order to ensure our future. We read Little House on the Prairie with childlike delight, never noticing that the little girl Laura was an illegal alien because her family was squatting on land that had been guaranteed to Native Americans by law and treaty. We rarely acknowledge the twin forces of hope and need that drove her family to become migrants.

Today, I live in Central Europe, a land so settled and stolid that you would think it quite understandable that people here have even less empathy for immigrants.

But wait...

Have you forgotten so quickly? It may sound like ancient history, but it is only a single generation since the land where I stand sent refugees fleeing, risking their lives and the lives of their children--desperate escape.

Creative Commons image by André Hofmeister

My husband is fifty and he grew up in a village just four miles from the Czech-Austrian border. He remembers well the soldiers who came into the border villages to train children, including him and his younger brother, to watch for possible defecters fleeing their totalitarian homeland. The children were issued binoculars and notebooks by the army and taught to record the license numbers of all strangers.

Today the Czech Republic is among the most anti-refugee countries in Europe. From newspaper accounts, we have yet to accept one single refugee from Syria. And yet we've had demonstrations condemning the refugees... preventatively. "They are different," the Czechs say. "They are not like us and they will change our culture."

And I fly back in memory.

I was a sixteen-year-old girl, barely old enough to understand and I was an exchange student in Germany just a few miles from the old Fulda Gap. The border was open then but it had only been that way for just three short years. And my best friend was an illegal migrant from Czechoslovakia. He played the guitar and spoke in a beautiful language I couldn't understand. He told stories of a hidden country the world knew little about. The German family where we lived kept him hidden in the basement--a debt paid to a family member left behind on the wrong side of the Iron Curtain and still something to be ashamed of.

(This is a powerful, short clip from a documentary about Czechoslovak refugees risking being shot to flee across the border into Austria in the 1980s. The quote in Czech in the video translates as, "It would be life or death, both or neither of us. That was all I could think of at the time.")

At my German school, I quickly learned not to speak about my friendship with the Czech. It was considered very odd that I would want to befriend such backward people. At home, the host family forbid the Czech man to speak his language to a Czech maid we knew. Everything from the east was considered less-than and possibly dangerous.

Today that man is a father of three with his own house and a teaching job. And he is afraid of refugees.

A cousin of my host family also came around sometimes, a guy from East Germany with intense fierce eyes. It was the family secret that his mother had been accidentally left behind, when the family fled from the east twenty-five years earlier. I thought he hated me because I was an American--the way is eyes would bore into me.

Creative Commons image by Freedom House of Flickr.com

He wouldn't talk about it, but the others said he had fled over the Czechoslovak-Austrian border before it was open. He had escaped through that net of children with binoculars and soldiers with automatic weapons to join his aunt's family in the west. He had risked his life when he was little older than me--still a kid--because it was the only hope he could see in the world.

I will never forget the look in his eyes. I have seen it now many times over and I know now that he did not hate me. It was just fear, desperation, confusion and the expectation that I would hate him. You see the same look in the eyes of refugees today, people who have been forced to run from their homes by war, starvation, imprisonment or oppression. They are not entirely without understanding. They know that many people where they are going will fear and despise them. And yet they have to go, and so their eyes come to have that look of intensity.