The hidden threat from AI art and writing

/Even those of us who live under metaphorical rocks—mostly constructed of the stacks of books we’re reading—have heard of the controversy surrounding AI writing and art. Actors and writers went on strike in Hollywood for three months. Artists are protesting across the internet.

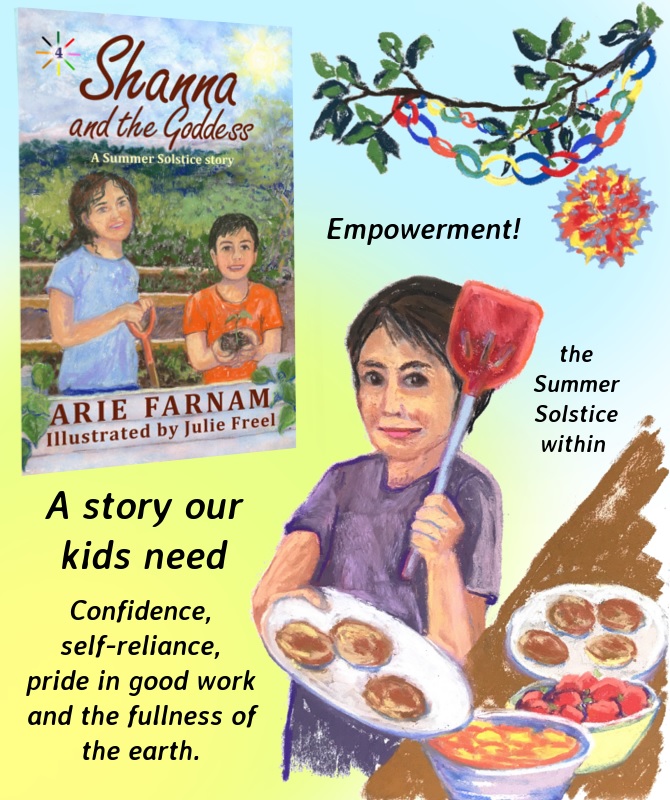

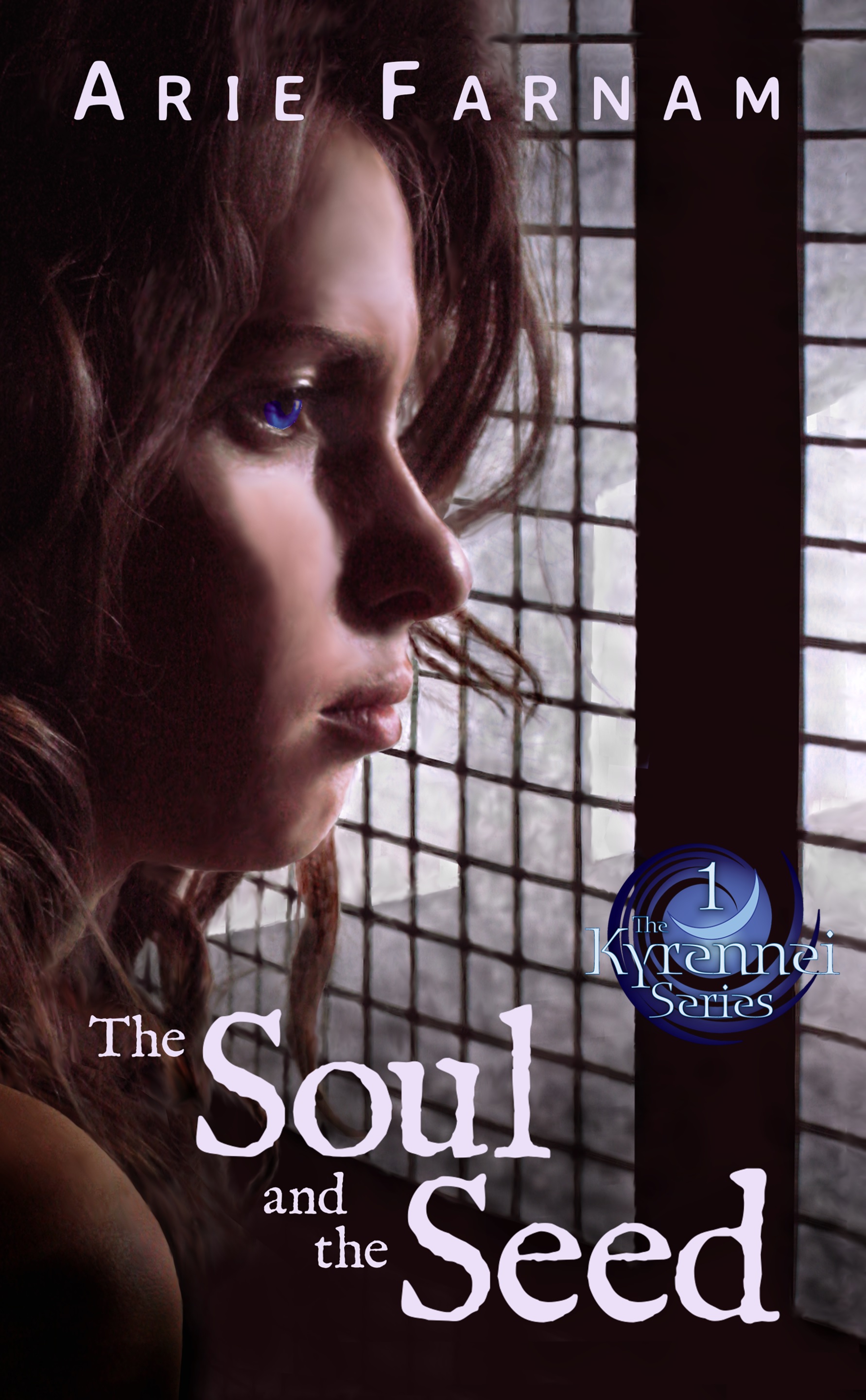

To many outside these fields and even to some within them, the narrative goes something like this: Artists and writers work hard to create masterpieces and they are already under-compensated. Now companies are going to use AI to analyze vast piles of copyrighted material and generate similar work without compensating the artists and writers who produced the original art and books used in the analysis. If you love the work of artists or writers, you should be upset about this because your heroes are going to be robbed.

And that isn’t wrong. The fields of art and writing are notoriously competitive and underpaid for 99.99 percent of those who work in them. Adding extra ways for companies to unfairly exploit professional artists and writers is a terrible idea.

Creative Commons image by mu hybrid art house

But all that sounds theoretical and most AI experts, when pressed, will tell you that it hasn’t really happened yet. Well-known artists and writers haven’t actually lost any money to this phenomenon… yet. And at that point in the conversation, most people who paid attention at all, tune out.

It’s a theoretical future problem. I’ve got 99 problems that are acute today.

However, we almost never hear about the actual harm being done right now by AI in the fields of art and writing. It’s likely that that is because it does not affect anyone wealthy or well-known. It doesn’t plagiarize great or original works. It just silently takes the jobs which artists and writers don’t love but which provide the bread and butter for 90 percent of us working in these fields.

Take for instance the little line-drawing illustrations of goofy no-name characters in a child’s math book. A. Who drew those? B. Was that person a real artist? C. Could just anyone draw them?

Answer key: A. Someone you’ve never heard of. B. You better bet they are. C. No way! I dare you to try.

Take the description of a product or service on a website or in a brochure. Likewise, someone wrote that. They might have been just regular staff, but if they are, the copy is probably lackluster. They were most likely a writer or a writer in training. If that ad is any good, chances are that the person who wrote it dreams of writing a book or a short story.

There are thousands, even millions of these little unimportant writing, drawing and design jobs in our modern world. You never hear the names of those artists and writers and you’d have to dig very deep into the small print of credits to find them, if they are even listed. These writing and art tasks are sometimes combined with other roles in the corporate world, but the writing and art aspects of the jobs are often the part that gives the person doing them a sense of purpose and self-actualization.

And many working artists and writers use jobs like this as a “day job” to tide them over in hopes that they may someday be able to make a living creating independent art or stories. And many of those who do “make it” and become professional, full-time artists and writers got a lot of their experience and training from these minor, unsung creative tasks.

AI is taking these jobs. Not theoretically in the future, but right now. AI may not yet be able to create cutting-edge art or completely flawless, nuanced text. But it can and does create simple line drawings for every type of publication under the sun and rough drafts of a lot of technical and advertising copy. Writers become editors of AI text. Artists become technical designers, plugging AI-created images into templates.

And that may not sound so bad, until you realize that with this technology, one writer can edit the text that ten would have previously written from scratch. One artist can format images in an hour that would have previously taken them ten hours to create on their own.

I hear about the results of this daily. A friend mentioned off-hand that her sister who used to write speeches for a major corporate CEO as a full-time job is so “successful” that the jobs of seven other writers have been consolidated and she now writes remarks for seven CEOs and their public relations departments. My friend thought this meant her sister was moving up in the world, but the job she was doing before was also a full-time job. She got only a very small raise to do the jobs of six other writers. And this is because the companies she works for use AI to generate text, which she merely refines.

And the six other writers? They had to find other jobs and given that this is happening across the industry, the chances are that they didn’t find jobs that entail creative writing.

These basic creative jobs are disappearing. They aren’t the jobs artists and writers most want. They aren’t particularly fun or all that creative. They’re just jobs that use and foster writing and artistic skills, jobs that have provided basic livelihoods ever since the invention of the printing press.

No one gets very upset about this in public discussions about AI because those weren’t the sought-after jobs anyway. But the cost is going to be high.

First, writers and artists who have not yet broken into full-time professional work in their fields will have to find other jobs, often more exhausting jobs, often jobs where they can’t utilize their primary skills in writing and art. It isn’t the end of the world, but for many of us these jobs provided not only a bit of self-respect but also a way to keep our skills sharp even when life and “the market” didn’t allow for much time to pursue our writing or artistic calling.

Second, there will no longer be much of a training ground for new artists and writers. You’ll either learn to be outstanding at your craft and then become well-known or you won’t. And this will exacerbate the trend of writing and art being a business where you have to be born into the right family or socio-economic circumstances to have a reasonable shot at a career. It will feed the monstrous celebritization of writing and art, in which a tiny elite make fabulous amounts of money, while everyone else makes little or nothing.

Third and possibly most insidiously, with even fewer paying jobs that utilize the skills of creative writing and artistic expression, schools and universities will eventually cut back their art and writing programs. Surely, people will still dream of being artists and writers and some education in those fields will be available for those who can pay. But when the social usefulness of a trade fades, so does it’s infrastructure.

For me, this is not theoretical, because I saw newspaper journalism undergo a preview of this process twenty years ago. For most of the twentieth century, it was possible for writers, artists or photographers to make a basic living producing material for the many magazines, newspapers and other periodicals that connected the world of that era. There were writers, artists and photographers who were regular employees of these publications, but generally the insatiable hunger for variety meant that there were quite a few freelance opportunities as well.

It was still a competitive and risky business to be in, but it was one that gave many creative people an outlet for expression, a start in the profession and a basic income. Both the expansion of the internet and changes in international news focus after 9/11 changed all that within a few short years in the early 2000s. And nine out of ten of my colleagues in newspaper journalism had to go looking for other jobs.

Many went into completely different fields. Others took up copywriting, technical writing or graphic design in the online world—shifting to fewer, less independent, more constrained jobs. When old journalism colleagues get together, someone will often quip about our profession having gone the way of blacksmithing—meaning that technological and social change has rendered us obsolete.

At the time, many hoped that this was only a market shift. Creative jobs would come back in a different form, they said. We’d be able to write website copy and technical manuals or design ads. And many have, but those were not really new jobs. They existed before and the writers and artists pushed out of mainstream journalism were joining an already crowded pool of content providers in the advertising and technical fields, which migrated online.

In the past twenty years, I have not seen much recovery in the availability of journalism jobs. Mostly the growth has been in the least creative types of jobs that still require some artistic or writing skills—such as technical and advertising copy, jobs where the artist or writer has zero say about the content and is nothing but an engine of creativity, directed by executives.

Just as our old journalism jobs didn’t return and better jobs didn’t replace them, I don’t believe the assurances that AI will only take the drudgery out of art and writing and leave us with the fun parts.

Certainly, those who are at the top of these professions have little to fear from AI at this point. But most paid journalism jobs disappeared twenty years ago and stayed gone. These unsung creative jobs in copywriting and basic art and design are being gobbled up by AI because our societies have chosen not to regulate the way companies can use intellectual property to train AI. That train has already left the station and reversing it at this point would be an immense task.