Every profession has it's secret language and writing is no exception.

I'm putting together a collection of tools and inspiration for writers here on my blog site. And one of the first things that goes in that toolbox are the terms that writers use to talk about writing. I'm not talking about things like "grammar" or even what kind of keyboard one should use. I'm talking about the professional terms that are crucial to development of the craft and surviving in the world of authors.

I have been writing since... I don't even know when. Maybe since I was seven and my family took a trip to Mexico and I wrote bits and pieces about it in a scrapbook. When I was a teenager I dabbled in fiction and then I turned to what I thought of as serious writing, i.e. newspaper journalism. While working as an international correspondent in places like Kosovo, the Ukraine, Ecuador and Bangladesh, I also took writing classes and joined writer's groups.

And from all those years of experience, I know for certain that writers get better. I haven't slid off the fence yet in the argument over talent versus experience. I think there are some assets that are handy to get genetically to be a writer. But I definitely know that no amount of inborn "talent" will make up for lack of practice and knowledge.

And the most basic knowledge, as with any profession, is knowing the professional lingo. That's not just so that you can talk to other writers and sound like you know what you're talking about. Each of the terms I will list here packs a key concept that writers use as surely as a carpenter uses an electric screwdriver or a sander.

There are probably too many words I could list, so I'm going to just start with those terms and concepts that I have seen writers struggle with. I'm going to be teaching writing workshops this fall, so I am likely to add to the list as I go.

Genre woes

I'm not going to cover everything to do with genres. That's a huge topic but here are the terms that I have seen cause misunderstandings.

Genre-blending and genre-mixing:

Genres were made up by the publishing and bookselling industry. It was an attempt to get people to buy more books and it worked. If a type of story was successful, publishers put out more of that kind of book and booksellers put them on a shelf next to the successful books of similar type.

But these categories are essentially arbitrary. Someone somewhere decided that all stories that hinge on a character trying to find out a secret (such as who done it or where is it?) should be put on a shelf together. And then someone else decided that stories where a romantic relationship is the central point should be on another shelf. Thus the mystery and romance genres were born.

That may be simple enough but then came science fiction, fantasy, chick lit... And now we have steampunk, new adult and dystopia. Each of these "genres" has a description but they are often indistinct and not mutually exclusive. For the publishing and bookselling industries this is a problem.

When a writer (I'm looking at you Morgan Daimler) writes what at first sounds like a mystery but puts it into a fantasy world with a romantic relationship as central to the action and aims it at a specific cultural or religious group of readers, your local bookstore is in trouble. They don't know where to shelf it and if Daimler had shelved hers in mystery, where it seems to belong on first inspection, I never would have read it, because mystery is one of the few things I almost never read.

Enter the age of Amazon and similar retailers. Thanks to complex algorithms, we can now categorize books much more precisely and readers can find what they want to read based on a lot of factors - the reader's age, culture, gender and interests as well as the the type of story or what is central to the plot. This means that writers and readers no longer have to stick to these arbitrary and ultimately claustrophobic categories known as genres.

The result is a lot of genre-blending and genre-mixing in which writers take interesting facets of various genres and come up with something fresh and new that would have been "impossible to publish" ten years ago.

Dystopia:

I would like to define one particular genre because I have seen several online forums where significant confusion over the definition reigned. Thanks to the popularity of books like The Hunger Games and Divergent, writers love to claim that they are writing dystopia these days.

The problem is that the virtual shelves of dystopia have been inundated with piles of books about zombies, vampires and apocalyptic disasters. While there is nothing inherently wrong with this fiction, most of it isn't dystopia.

The quick and dirty definition of dystopia is as easy to formulate as that for the romance genre. It is said that it isn't a romance if you can take the love part out and still have a plot. Similarly, it isn't dystopia if you can take the socio-political problems out and still have a plot.

Dystopia is the counter to utopia. It is society gone wrong in some crucial way. George Orwell is often held up as the father of the dystopian genre and a lot of dystopia is like Orwell's work, overt social commentary set in a totalitarian society that exaggerates certain elements of our own world to show what could happen if we continue in some unwise direction. Some dystopia is more subtle, showing an outwardly ideal society, often set in the future but showing how an individual can be harmed even within an ostensibly perfect system. More rare is dystopia set in our times and essentially in our world but highlighting particular aspects of contemporary society as dysfunctional.

Steampunk:

Steampunk is a relatively new genre that includes stories that take place in a society that is not high tech but includes some technological advances. Some of the technology tends to be a bit fantastic, such as flying machines with flappable wings that run on steam engines. But it isn't all silly. Some steampunk is set in a future world where much of the high technoogy has broken down for one reason or another. Some of it is set in a fantasy world that is neither entirely modern nor entirely medieval.

New Adult:

New adult is sort of like a genre that occupies the crack between Young Adult and general adult-level genre fiction. I like the theory of a genre that appeals to twenty-somethings but alas New Adult has been largely taken over by stories set on or around college campuses that involve romance. It should legitimately be called New Adult Romance now, but for the time being the going term is New Adult.

Narrative nonfiction:

Narrative nonfiction is a writing style as well as a genre. I have again seen a lot of confusion about it in the online world. Just about any sort of nonfiction can be written in narrative form, meaning written as if it were fiction... as a story. A lot of the best history books are being written this way as well as memoirs, self-help and inspirational books. There are also some pretty good technical how-to books written with at least elements of narrative style.

Style and writing terms

This is not a comprehensive list, just the things that I have run into in discussions with writing students, writers or editors in the past year.

First person

I am now writing in first person. I personally prefer first person narratives, even when I'm reading fiction and the author isn't really the character talking in the book. I like first person because it brings the reader right into the story intimately. I know there are disadvantages to it though. For one thing, the reader has to take my word for it. If I had written this paragraph in third person, I could have made the advantages of first person sound much more universal and authoritative. This way you just know that I like it.

Second person

You may be reading this either to stock your writer's toolbox or simply to be entertained. Whatever your reason, you are now reading a paragraph written in second person. Second person is what happens whenever you the reader are the primary character in the narrative. You can try it in fiction if you want but you'll find that it is exceedingly difficult to pull off well.

Third person

Most writers choose to write in third person. It's probably the most versatile point of view in terms of the types of voice and tone that the writer can employ. Third person simply means that the story is about a character who is named and referred to as he, she or it. The reader isn't addressed directly and the narrator remains in the background, never speaking directly about him- or herself. Arie Farnam wrote this paragraph in third person, which creates some minor problems when it comes to avoiding the passive voice.

Passive voice

Passive voice is often misunderstood. I am amazed at the number of writers and editors who are confused by what is passive and what isn't passive voice. The phrases above with "misunderstood," "amazed" and "confused" are all written in passive voice, as is this sentence.

Here, let met me fix that. (Because passive voice is evil, right?) Many people misunderstand passive voice. I see a lot of writers and editors who confuse awkward sentences and passive voice. I wrote the last three sentences in active voice.

If you go to a high school composition class, you will be told to avoid passive voice like the plague. And it is a good thing to do at the beginning. Beginning writers almost always overuse passive voice and it is very helpful to try to avoid it. The vast majority of sentences will be more concise and interesting in active voice.

The easiest way to avoid passive voice is to go through your writing and look for passive adjectives (adjectives that describe something that has happened to the noun, like "written", "flown" and "misunderstood.") Try turning these sentences into active sentences and see if they're better that way. Usually they will be.

Biut there will be times when they aren't. Passive voice isn't bad to the bone. There are reasons to use it. Laziness is, however, the most common reason it is used and that isn't a good reason. When I said "Passive voice is often misunderstood," I was avoiding having to say who misunderstands passive voice. I could have been doing that as a way of being diplomatic, which is sometimes a good idea, but I was surely also doing it partly because it is easier to hint that some mysterious "them" out there misunderstands passive voice than to do the hard work of thinking about exactly who does.

I've recently had editors tell me things are passive voice when they aren't. Past perfect and present perfect sentences like "She had read all of my books" and "I've been working at the store" are not passive. The are easy to confuse with passive because the form of the verb used in those tenses in English (Fun fact: and in Russian!) is the same as the passive adjective used in passive voice. The linguistic term for this type of word is "the past passive participle." You really wanted to know that, didn't you?

Writing for a living

There is a lot of hype about writing as an entrepreneur lately. I get it. Writers need to think like business people in order to succeed. But the terminology can be scary. When you get right down to it "an author entrepreneur" is a person who makes a living from writing books.

Self-publisher or indie-publisher:

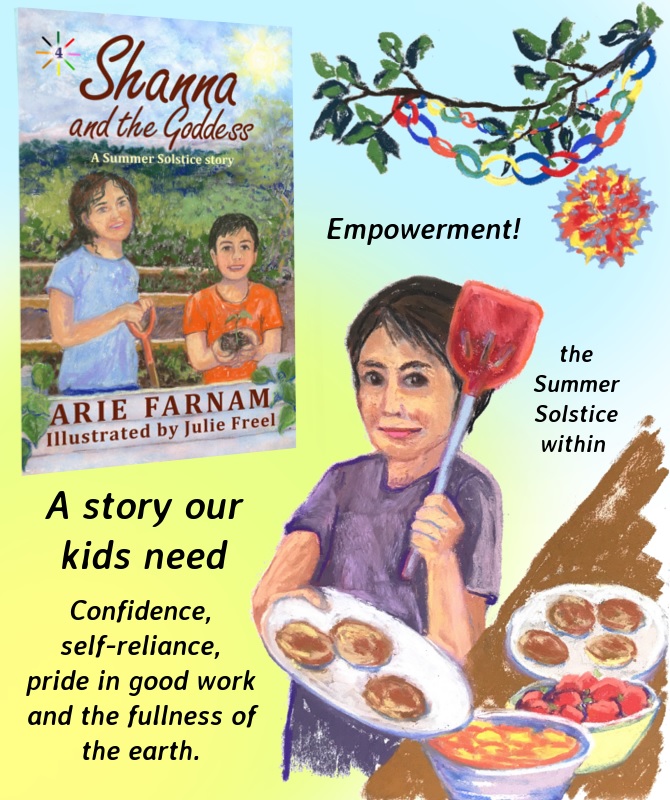

These two terms get used interchangeably most of the time. Indie implies a bit more rebellion and a desire to keep independence even from retailers and other services. There are self-publishers who would gladly sign up with someone who would do a chunk of the business side of their work at the drop of a hat, in order to have more time to write, and independence be damned. But in general, both self-publishers and indie-publishers are writers out there trying to do serious writing and publishing, often as a business. Their primary goal is usually not fame and fortune or the kick of seeing their name on a book. And many never do see their name on a "book" because they stick to ebooks. It reminds me a bit of the culture of international freelance journalists of the 1980s and 1990s, minus the worn out shoes. It is chaotic and only the hardiest survive for long.

Traditional publisher:

A traditional publisher is a company that makes a profit from actually acquiring rights to publish books, publishing them, selling them and paying authors a royalty. There will always be some overlap in these descriptions but a self-publisher doesn't become a traditional publisher just by giving their publishing "company" a name that is different from their author name. Neither does a vanity publisher become a traditional publisher by accidentally selling a few books and actually paying a royalty once in a blue moon. A traditional publisher has to turn a profit in the traditional way.

Vanity publisher:

A vanity publisher is a company that makes a profit by charging authors for publishing services. This isn't to say that a vanity published book has never sold a copy or made the author a cent. Some probably have but the difference between a traditional publisher and a vanity publisher is that a vanity publisher charges for things that a publisher traditionally covers. Vanity publishers don't pay advances and they don't have very high standards (if any) about what they publish, so they'll publish just about anything. They also don't promote books or help in selling them in any way. But traditional publishers often don't do that last very much either.

Proof copy:

This refers to a printed book that is sent to you buy the printer (or publisher possibly) for you to check for mistakes before the book is approved as final. Proof copies usually have a page or a stamp that says "proof" on it, so they can't be sold as "regular books." Printers often charge less for them and so they don't want you just ordering a bunch of proof copies and selling them as if they were the final book. Proof copies can be sent to reviewers to get early reviews.

Ebook formats:

When I first got into indie publishing I was a bit worried by all the talk of formatting headaches and woes. I thought this meant that formatting was going to be as hard as learning webdesign had been. It wasn't.

Maybe it's just me but I don't find formatting to be that terrible. Okay, some of the work can be tedious. If like me, you started writing in MS Word without a care in the world and just typed, you might well have used tabs to indent your paragraphs and then after a few paragraphs Word picked up on that and started automatically indenting. But when you started a new chapter, you had to go back to pressing the tab button. This is the dumb way to do things, Arie... Yes, I know but I didn't even know I was writing something serious at first. So, anyway, if you foolishly did that, like me, then when you're finalizing your work, you have to go back and weed out all the tabs. Tabs are a big no no in ebook formatting. Put on some good music, get into a meditative mood and skim down the left-hand side of your screen and delete all tabs. Not hard, just tedious.

There are more complex parts of ebook formatting and I"m not going to cover them all here, but the essential thing to know is that, if you can organize a kitchen cabinet, you can format an ebook. Know the most important format names.

Mobi is the standard Kindle format.

Epub is the format for Android-based systems.

Ibooks is the Apple format.

I use Scrivener to organize large projects and Scrivener converts to Mobi and Epub formats easily. You can also now use Smashwords to automatically convert and they'll do Ibooks too. But in either case, you have to start with a very cleanly formatted manuscript. Do not try to insert extra lines anywhere. Learn to use page breaks. You can run into trouble with graphic elements and things like drop caps. So, it is best to avoid those until you are used to formatting.

Cover design: