Paying attention: The lessons of crow or raven

/When I was a kid, I knew I wanted to live close to the land, to live out of the city, grow a garden and even raise chickens. I wasn't just being romantic. That is how I grew up and I knew about the work involved.

Still my reasons at first were not the same as the reasons of grown-ups. Living close to the land is a bit healthier, but it's also harder on the body and often plenty heavy on the mind. My own reasons had more to do with where I felt most alive.

Creative commons image by Igor Shatokhin

When we experience something with all of our senses, we feel much more alive. If you live close to the land, you have to be out in all weather--feeding animals, digging in the earth, planting, harvesting and fixing things.

Often it doesn't seem pleasant but you feel, smell, see and hear everything. As long as this is part of your survival, rather than just a good-for-you walk in the midst of an otherwise dull day, you won't be bored.

Kids often understand this even if they live in a very artificial environment. When my young son marvels at the return of snow and only vaguely remembers when it was last here nine months ago, he tastes it, smells it, stands listening and then runs around wildly flailing in it.

"Mama, will the snow always be here now?" he asks.

His sister, two years older and oh so much wiser, sneers, "No, baby, it will only stay until the trees want to wake up."

While the squabble over who is a baby goes on in the doorway, the cold wind swirls into the house and a crow (or possibly a raven, my eyes aren't good enough to tell the difference) quarks from the young oak in front of the house.

Many grownups today barely notice the first snow fall, let alone a single bird in a tree. But I notice. This bird with its solid black feathers is interesting and important, just like the traffic signs on the road. It is part of paying attention and being fully alive.

Creative Commons image by Byrion Smith

Crow and raven as symbols

Fortunately, it doesn't matter much that I can't tell if it is a crow or a raven. They are both considered important and even magical birds by people all over the world. Europeans, Native Americans, the ancient Chinese and the ancient Egyptians all saw the crow and raven as symbols of real-world magic, the mysteries of the unknown, and possibly death, as well as transformation, healing, wisdom, protection and prophecy.

While some cultures connect this bird to the sun and others to the dark of a moonless night, there is no human culture where they are native that does not see them as powerful, mysterious and noteworthy.

Modern pop culture suggests that all symbols of the crow and raven must be sinister. But that wasn't traditionally the case. Our great grandparents might have told us that the appearance of these black birds is a reminder to pay attention, to follow your intuition, to use your personal integrity, to reserve judgement against people, to question your assumptions, to think independently or stand out from the crowd.

Some people believe that crows and ravens can bring messages from another world, perhaps from ancestors. Others believe the bird simply shows that something is going to change or that it asks us to be faithful despite changes.

How do they live?

Crows and ravens can eat almost anything and adapt to very different environments. Crows always keep a mate but often live in groups. Ravens are faithful to one mate for life and often live in pairs. This is one reason why these birds symbolize faithfulness to many people.

Creative Commons image by Jennifer C, of flickr.com

Both types of bird are very intelligent compared to other species. Their cawing, which sounds pretty raucous to us, is actually a sophisticated language. Different kinds of cawing mean different things. Crows will often build false nests to fool predators and to protect their young. When they are in a group they will let one member check out any new object while the others watch and learn. When they eat as a group, they post sentries to warn of danger. They will even warn other animals, and especially deer, with a lot of noise when hunters are around.

These are all reasons why these birds came to be symbols of wisdom and caution. They are not dangerous themselves. Instead, if we are careful and pay attention to them, we can learn to protect ourselves both physically and intuitively.

What do they teach us?

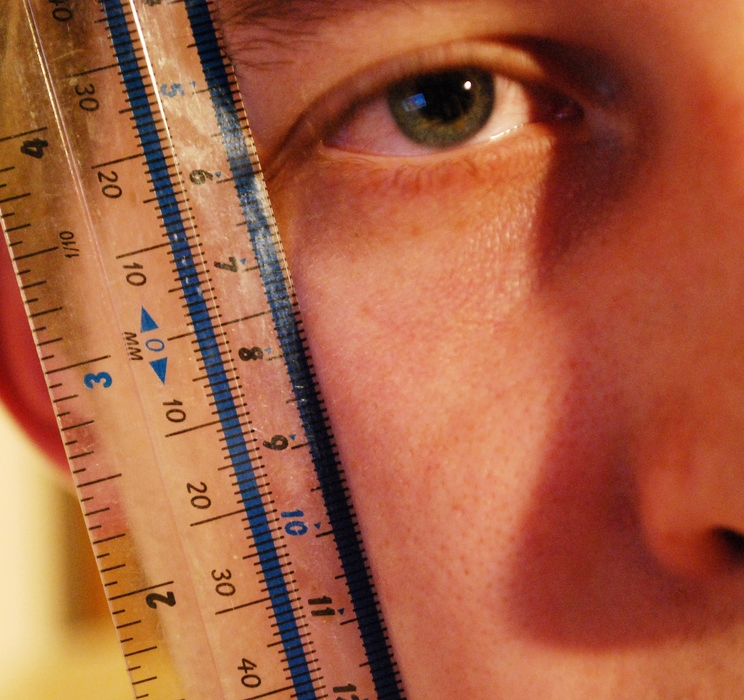

Crows and ravens have shown humans how to think things through and question our assumptions. Over time, many people came to see just the appearance of one of these birds as a reminder to look beyond first appearances, to avoid quick assumptions, to measure every thing based on an objective standard, to explore the unknown and to cross physical and mental borders.

In a media-saturated world it is often difficult to tell the difference between your prejudices and true intuition. These birds are a good symbol to keep in mind. Many cultures believe that seeing a crow or raven means you should spend some time in introspection, make sure things are as they seem or try to remember what you may have forgotten or left behind in your hurry.

Different cultures have very specific omens associated with crows and ravens, often depending on which direction the bird is from you and what time of day it is. It may be that these symbols work only in the place they come from. It is more likely that these omens or "rules" were devised to try to explain the intuitive messages of the birds in a logical way. The problem with this is that intuition defies logic. It might then be more effective to observe the specific case without much reference to rules about whether the bird is on your right or on your left or if it is morning or afternoon when you saw it.

It is the general reminder of caution and the need for intuition that is universally understood about crows and ravens. When so many diverse cultures with long and learned histories arrive at the same conclusion, it is worth paying attention.

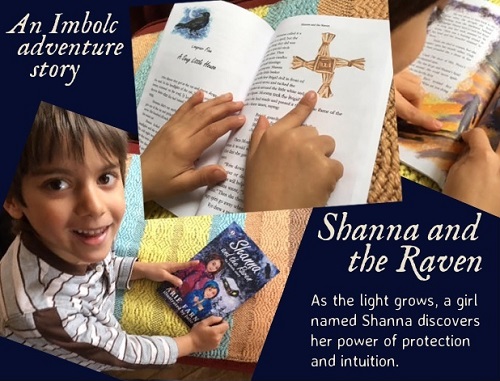

A story about intuition and a raven

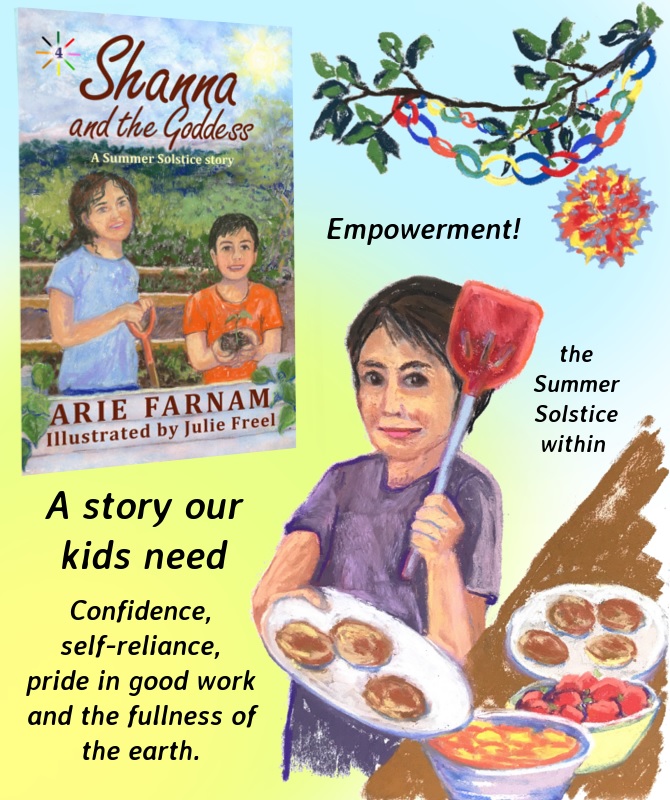

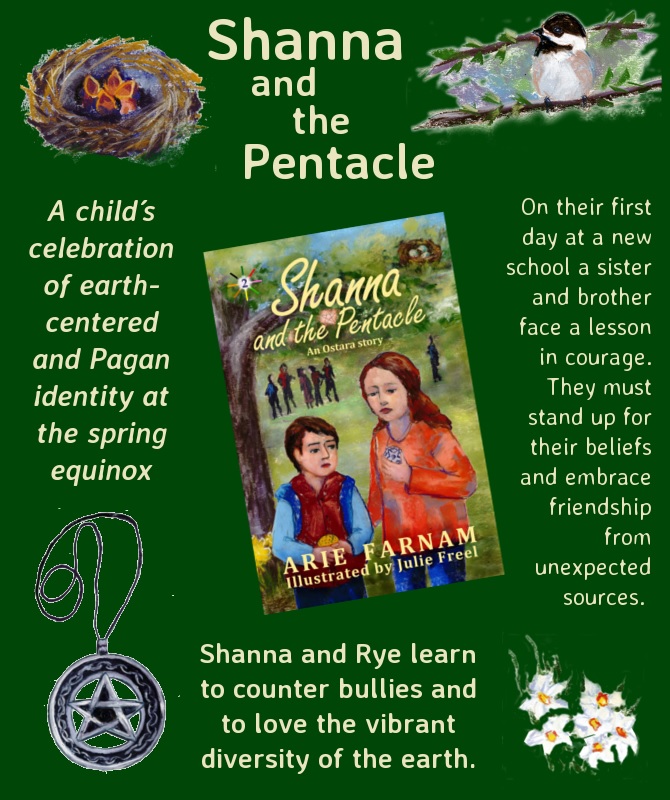

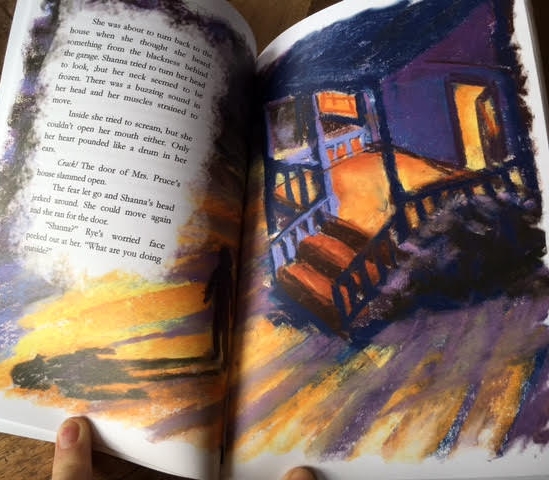

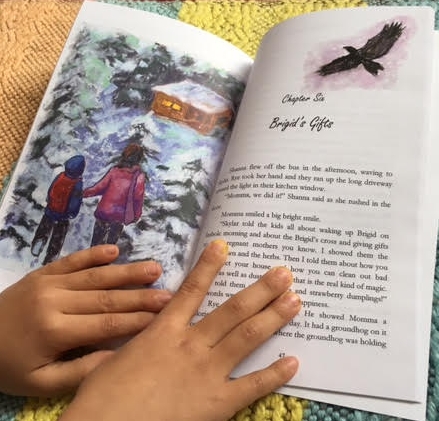

A couple of years ago, I wrote a story for kids and adults that gives a real example of how this can work. The story is Shanna and the Raven. It's about a girl named Shanna and her brother Rye, who see a raven after they meet a neighbor who makes them feel strange. The story is a tiny bit scary but it shows how intuition can be a powerful protective tool for both kids and grown-ups.

Shanna and the Raven is also a story about this time of year. Shanna and Rye celebrate a very old holiday called Imbolc, which is about intuition, inspiration and prophecy, just like the raven and crow. This holiday comes on February 2 and you can try out their recipe for strawberry dumplings, which is really delicious, or make a doll of the Irish goddess Brigid using their instructions.

You can start reading the story and see many of the beautiful illustrations by Julie Free at the bottom of this page.